American Land, American People

Exhibition Information:

June 2020 - Present (on view)

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Richmond, VA

Curated by Johanna Minich, Chris Oliver, and Leo Mazow.

Collaborator of American Land, American People, as part of my Sameul H. Kress Interpretive Fellowship (2019-2020).

To visit the online exhibition, click this link here.

June 2020 - Present (on view)

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Richmond, VA

Curated by Johanna Minich, Chris Oliver, and Leo Mazow.

Collaborator of American Land, American People, as part of my Sameul H. Kress Interpretive Fellowship (2019-2020).

To visit the online exhibition, click this link here.

Control of the land was a core tenet of Euro-American aspirations throughout the foundation of the United States, and particularly during the era of Manifest Destiny in the mid-19th century. However, the land was and continues to be Indigenous Americans’ most precious resource. For Native inhabitants, land and people are inseparable; the cosmos is a living being and, as such, demands similar respect. These values were poorly understood by white settlers whose philosophy was deeply rooted in the Christian belief that land and the natural world were meant to be subjugated and exploited. Consequently, the 19th century witnessed an especially violent clashing of these diametrically opposing worldviews.

In the hopes of offering and striving towards a more complete, inclusive narrative of American art and cultural history, VMFA presents both here and in the American gallery combinations of Euro-American and Indigenous works. This featured exhibition American Land, American People specifically investigates various artistic interpretations and cultural values of American land and people through a comparative approach.

Spanning from the mid-1850s through the 1920s, works by Euro-American artists Asher B. Durand, Thomas Moran, Frederic Remington, and Walter Ufer communicate long-held assumptions about the American landscape as a site of celebration, nostalgia, and, often, exploitation. Their intimate examinations of nature served to promote a particular American dream – one based in conquest – while romanticizing and preserving in paint a quickly vanishing wilderness.

Confronting certain underlying messages of Euro-American landscape paintings, works by Indigenous artists Dyani White Hawk and Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith, among others, raise opposition to their artistic counterparts’ problematic painted narratives. Where the compositions by Durand and his peers elaborate on the prevailing expansionist ideology of their time, that of White Hawk and Quick-to-See-Smith point to how Euro-American landscape paintings commonly present selective, exclusionary histories in the first place. Contemporary Indigenous artists continue to add to this long-suppressed narrative, filling in centuries-old gaps in the true story of America.

Though each work may possess a distinct message, their grouping reminds us that land is much more than the soil beneath our feet. It is the inspiration for scenes of incredible beauty and a reminder of the residual trauma and ongoing resiliency of its displaced people.

LAND AS SUBJECT OR SPIRIT?: DURAND AND QUICK-TO-SEE SMITH

One of the most identifiable paintings by Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), a member of the later-attributed Hudson River school of landscape painters, Progress: The Advance of Civilization points to several aspects of cultural and social history, including ecology, Native American policies, railroads and the Industrial Revolution. Offsetting the locomotive, canal, townscape, and the log cabin at right, the Native American presence (relegated to the left foreground) reminds us of the sacrifices engendered by the “advance of civilization.”Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith’s (b. 1940) War-Torn Dress presents a legacy that is more cautionary than celebratory. The implication of a body inspires contemplation on Native lives lost and the contested spaces they occupied. Here, the Native presence is front and center, rather than relegated to a small detail. Placed prominently across the dress, “Your God, My God” proposes that within the fight over whose God is greater, all people reside in the Sacred, breathe the same air, and are of the same life force.

(Left) Asher B. Durand, Progress: The Advance of Civilization, 1853, oil on canvas, 58 7/16″ × 82 1/4 “× 4 3/8 “, Gift of an Anonymous Donor, 2018.547; (Right) Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, War Torn Dress, 2002, mixed media on canvas, 36 1/8″ × 48″ per panel, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2018.353a-b

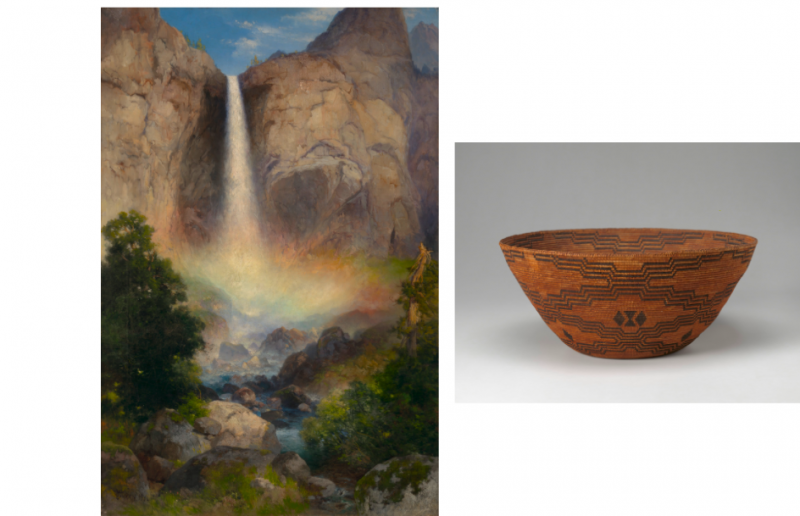

CONNECTEDNESS OF ALL THINGS: MORAN & CALIFORNIAN NATIVE BASKETRY

At the turn of the 20th century, Thomas Moran (1837-1926) was America’s preeminent painter of western landscape, capturing the compelling natural elements and vistas still inaccessible to all but the most intrepid explorers. This scene of Yosemite Valley in California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range, depicts the majestic Bridalveil Fall as it thunders down the face of a sheer granite cliff. Radiant in late-afternoon sunlight, the cascade strikes the valley floor behind a screen of iridescent mist, perhaps meant to symbolize the presence of a Creator. The role of the viewer is to witness this beauty, but the viewpoint suggests a separation between the observer and the observed.The Sierra Miwok people were some of the earliest recorded inhabitants of the Yosemite Valley. When Yellowstone Park was established in 1872, the Miwok and their neighbors were displaced from the valley and dispersed into the surrounding territories. Their connection to specific places is evident in one of their most enduring art forms: the basket. Using local fauna obtained from the valley, the baskets of the Sierra Miwok and other California tribes become a literal weaving together of man and nature.

(Left) Thomas Moran, Bridalveil Fall, Yosemite Valley, 1904, Oil on canvas, 30 1/4 × 20″ unframed, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Huntington Harris, 61.45.1; (Right) Unknown Artist (Sierra Miwok), Basket, late 19th-century, Willow and bracken root, 9″ × 18,” From the Robert and Nancy Nooter Collection, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Endowment, 2018.237

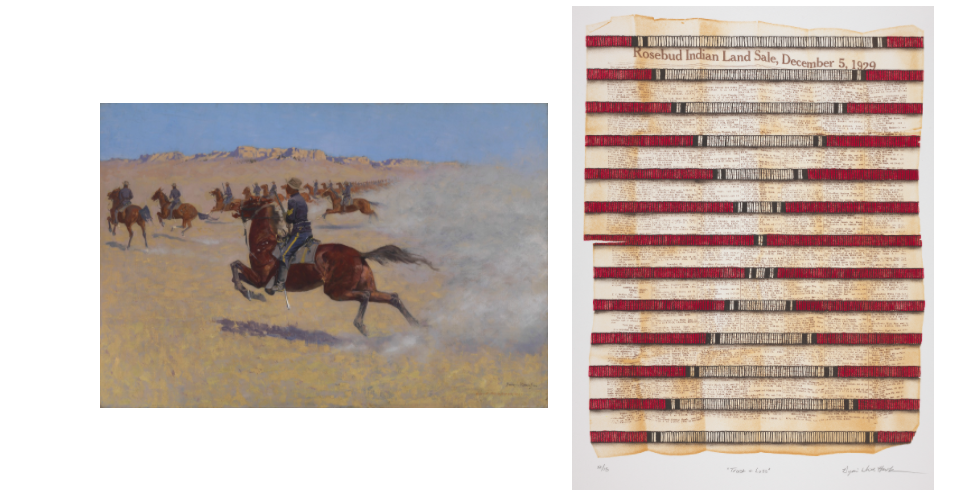

BREACH OF TRUST: REMINGTON & WHITE HAWK

This energetic painting of a military exercise observed by Frederic Remington (1861-1909) depicts a line of the advancing U.S. 9th Cavalry— an African American regiment known as “Buffalo Soldiers.” These men were formerly enslaved African Americans who enlisted in the U.S. cavalry regiments in segregated units under white officers. Poised atop his galloping mount, a keen-eyed soldier reins the horse as their two synchronized bodies rapidly charge across the broad, barren landscape. The American bison, vital to the culture of the Plains people, became a target for extermination when federal policy, and subsequent military efforts such as those of the Buffalo Soldiers, were created specifically to destroy the entire Native way of life.In Trust and Loss, Dyani White Hawk (b. 1976) incorporates a 1929 newspaper advertisement peddling lands from her own reservation. White settlers proclaimed the migratory habits of the Plains people and their lack of “ownership” of the land to be the behavior of godless savages. The Dawes Act of 1887 was a land allotment policy intended to bring about the rapid assimilation of indigenous people. Breaching numerous treaty provisions, Native lands were placed in a “trust” by the federal government, with tracts being assigned to tribal members and the remaining acreage offered for sale on the open market.

(Left) Frederic Remington, The Pursuit, ca. 1896-98, Oil on canvas, 27 1/4″ × 40″ unframed, Gift of the Estate of Sally D. Eddy, 76.20.1; (Right) Dyani Whitehawk, Trust and Loss, 2013, Four-color lithograph, 30″ x 20,” Funds provided by Margaret A. and C. Boyd Clarke and Aldine S. Hartman Endowment Fund, AA2019.8.6

(Left) Frederic Remington, The Pursuit, ca. 1896-98, Oil on canvas, 27 1/4″ × 40″ unframed, Gift of the Estate of Sally D. Eddy, 76.20.1; (Right) Dyani Whitehawk, Trust and Loss, 2013, Four-color lithograph, 30″ x 20,” Funds provided by Margaret A. and C. Boyd Clarke and Aldine S. Hartman Endowment Fund, AA2019.8.6EARTH, SKY, WATER: UFER & YATSATTIE

Walter Ufer (1876-1936) belongs to the Taos Society of Artists, the leading exponents of figurative painting in early 20th-century America. He joined the group in 1917, specializing in portraits of Pueblo Indians and vivid landscapes fluidly painted in a high-key palette with textured brushwork. On the Rio Grande melds his sensitive portrayal of a reflective native figure (his favorite model, Jim Mirabel) with the lushly rendered New Mexico setting. A strong supporter of individual freedoms and a devout Socialist, Ufer was deeply concerned with the plight of the Pueblo Indians and what he viewed as their centuries-long oppression.Pueblo potters were virtually all women throughout the 19th century. With the advent of the railroad and the ability of collectors to travel to remote locations in the southwest, potters were able to tap into an enthusiastic market for their wares. Ironically, traditional Pueblo pottery production almost died out at the turn of the century due to ethnographic and touristic collection of a majority of the older work that served as a tool for instruction and inspiration. By the mid-20th century, artists, both male and female, saw the opportunity to support themselves and their families with their ceramics and production once again flourished. Individual potters became known and sought after.

Cornmeal bowls, such as this one made by Eileen Yatsattie (b.1960) of the Zuni Pueblo for her mother, are used in the home and during religious ceremonials to hold sacred cornmeal and sacred water. The four terraced steps represent clouds in the four directions. Toads, tadpoles, dragonflies, and the water serpent are usually drawn on to represent prayers for rain and water. They are still being used today.

(Left) Walter Ufer, On the Rio Grande, 1927, Oil on canvas, 25 1/8″ × 30″ (unframed), J. Harwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund for American Art, 2014.183; (Right) Eileen Yatsattie, Cornmeal Bowl, 2000, Ceramic and pigment, 5 3/8″ × 7 7/8″ (overall), Gift of Edward A. Chappell, 2018.283